Intermittent fasting might be less effective than calorie control, finds a new study

Researchers write that this suggests that the size and frequency of meals — along with total calories eaten per day — have a bigger impact on weight change than the timing of meals.

A new study suggests that some people can achieve their weight loss goals without restricting their eating to certain times of the day. The frequency and size of meals was a stronger determinant of weight loss or gain than the time between first and last meal, according to new research published yesterday in the Journal of the American Heart Association, an open access, peer-reviewed journal of the American Heart Association.

According to the senior study author Wendy L. Bennett, M.D., M.P.H., an associate professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, although ‘time-restricted eating patterns’ – known as intermittent fasting – are popular, rigorously designed studies have not yet determined whether limiting the total eating window during the day helps to control weight. The main focus of this study was among intermittent fasting and calorie control which is more effective at weight loss.

Researchers say that calorie restriction appears more successful than intermittent fasting for weight loss.

Over the course of a six-year study, researchers found that people who ate a greater number of large or medium meals during the day were more likely to gain weight. In contrast, those who ate smaller meals were more likely to lose weight during this time. However, the time interval between the first meal and last meal of the day had no impact on people’s weight.

Researchers write that this suggests that the size and frequency of meals — along with total calories eaten per day — have a bigger impact on weight change than the timing of meals.

Researchers at three major health care systems – Johns Hopkins Health System, Geisinger Health System and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center – studied weight trends, daily food intake and sleeping/eating time intervals charted in a mobile app over the course of six months for 547 adult men and women with a range of medical conditions and Body Mass Index (BMI) categories.

These weight trends were compared to weights and heights recorded during previous clinic visits, up to 10 years before the study enrollment. Meal sizes were categorized as either large (more than 1,000 calories), medium (500 to 1,000 calories) or small (less than 500 calories).

Overall, most participants (80%) reported they were white adults; 12% self-reported as Black adults; and about 3% self-identified as Asian adults. Most participants reported having a college education or higher; the average age was 51 years; and the average body mass index was 30.8, which is considered obese. The average follow-up time for weight recorded in the electronic health record was 6.3 years.

Participants with a higher body mass index at enrollment were more likely to be Black adults, older, have Type 2 diabetes or high blood pressure, have a lower education level, exercise less, eat fewer fruits and vegetables, have a longer duration from last mealtime to sleep and a shorter duration from first to last meal, compared to the adults who had a lower body mass index.

The research team created a mobile application, Daily24, for participants to catalog sleeping, eating and wake up time for each 24-hour window in real time. Emails, text messages and in-app notifications encouraged participants to use the app as much as possible during the first month and again during “power weeks” — one week per month for the six-month intervention portion of the study.

Based on the timing of sleeping and eating each day recorded in the mobile app, researchers were able to measure:

- the time from the first meal to the last meal each day

- the time lapse from waking to first meal

- the interval from the last meal to sleep

They calculated an average for all data from completed days for each participant.

The study also found:

- The average time from waking up to eating was 1.6 hours

- The average time from first meal to last meal was 11.5 hours, and wasn’t associated with weight change

- The average time between the last meal of the day and going to bed was 4 hours

- Average sleep duration was 7.5 hours

Although the study found that meal frequency and total calorie intake were stronger risk factors for weight change than meal timing, the findings could not prove direct cause and effect.

Researchers found that people on a fasting schedule tended to be less active than before they started dieting, which might be one factor that kept them from losing weight.

In fact, some of the weight loss in the fasting groups came from losing muscle mass as opposed to burning fat, according to study results. This a major reason why intermittent fasting is less effective than calorie control.

Given these results, keeping up your physical activity and burning calories appears to be an important aspect of any weight control plan, suggested dieticians.

Some people benefit from intermittent fasting, such as consuming their meals in a 6- to 8-hour window. Two earlier studies found that eating within an 11-hour or 8-hour window was associated with weight loss. Both of these were small, pilot studies.

In contrast, a larger randomized controlled trial found that fasting for 16 hours each day wasn’t more effective for weight loss than eating throughout the day.

People certainly have had success by shortening their eating window to 11 to 12 hours. This can be done by stopping eating a few hours before bedtime.However, the people who end up losing weight with time-restricted eating are often the ones that end up eating fewer calories as a result of their eating time being limited.

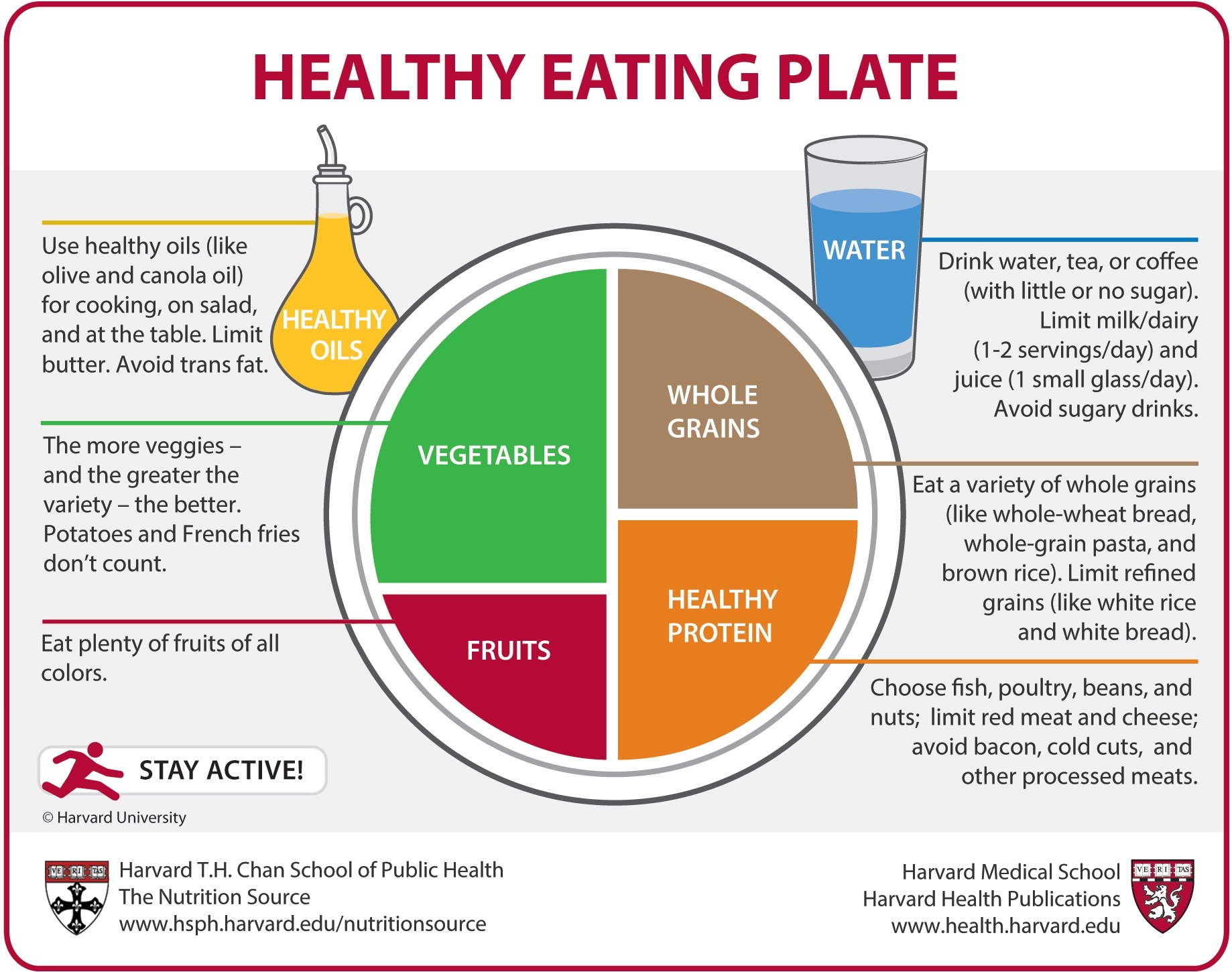

One approach that dieticians think may work for some people is to use a portion guide, of which there are many different versions, including a this one by Harvard University:

Portion charts like this helps people be more conscious of what they’re eating. Sometimes they may not realize that they’re eating such a large meal or that the meal has so many calories.

Whatever approach people take to meet their weight loss goals, clinical psychologists and eating disorder specialists caution against doing too much.

Extreme eating measures can result in disordered eating patterns, especially for those with predisposing biological or temperamental factors, such as genetics, increased anxiety or depression. This is again a major reason intermittent fasting is less helpful than calorie control.

It is recommended that people seek out professional support to help them meet their health goals, taking into account their specific circumstances, including their physical and mental health.

Using healthy and positive coping strategies — such as mindfulness, or healthy activities like social interaction or mindful movement — can be a way for people to follow through with their health goals, and not need to use unhealthy eating strategies to manage them.

Ms Kalinga

Ms Kalinga